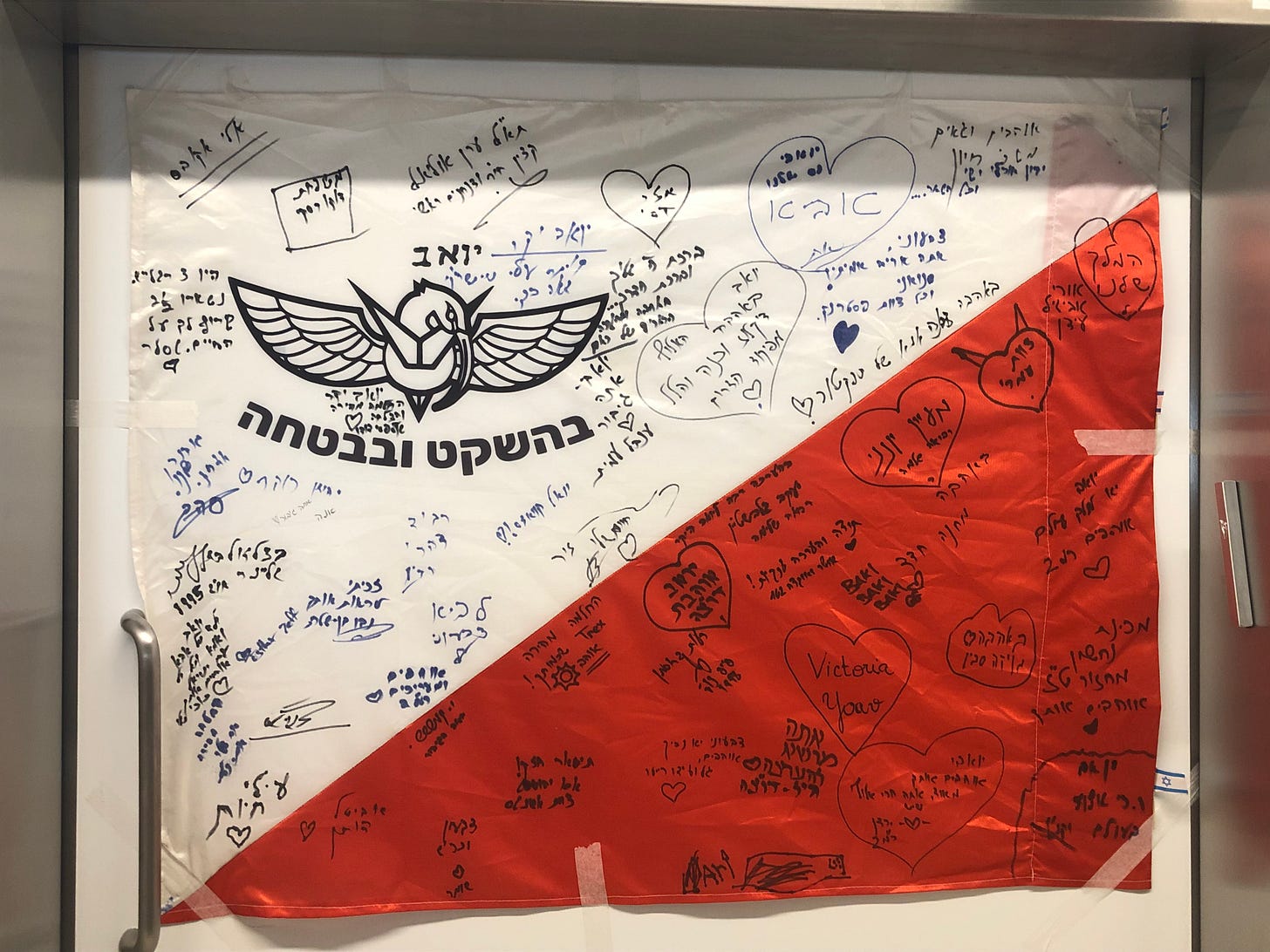

I had the rare and moving experience of visiting a severely wounded Israeli soldier this week at the Samson Assuta Hospital in Ashdod. Y, a Special Forces soldier, was nearly killed when a bomb detonated near him and his unit. A doctor in Gaza determined that Y would not have made it if transported to a more distant trauma center in Israel. Fortunately, the doctors and medical staff at this amazing hospital essentially, in the words of his mother, brought him back from near death.

What makes this story personal is that I have known Y since he was a young child, coming to one of our Ramah camps with his parents who worked on staff and with our Israeli shlichim for many years. As a teenager, Y would train hard at camp in the hopes of being accepted to an elite unit in the IDF. He succeeded and he and his comrades having been doing what is necessary to assure Israel’s survival and safety for years.

Thank God, Y has left the ICU. He has had over 20 surgeries; he is now able to speak and eat regular food and he will soon move to a rehab hospital. He hopes to return to his apartment, girlfriend and a future career, though he notes that “sometimes life takes a different path than planned.” (He wishes he could have served more than four weeks in Gaza, that he can return to Gaza, and that he would do it all over again). Y also joins the expanding ranks of Israelis who are now considered disabled. Y is now an amputee. He feels “lucky” that his leg was lost below the knee and that he will soon be fitted for a prosthetic leg. He is incorporating this new aspect of Y—his disability—into his already multi-faceted character. He is determined NOT to let his disability define him.

Y is not alone. Israel is “welcoming” new members in to the disabilities community almost daily.

According to the Times of Israel, the Health Ministry reports that as of the middle of December, an extraordinary number of Israelis–10,580–have been wounded in the war with Hamas in Gaza, attacks by Hezbollah along the Lebanon border, and terrorist attacks in the West Bank. The latest figures provided by the Defense Ministry indicate that 6,125 of the wounded are IDF soldiers and members of the Israel Police and other security forces. Of these, 2,005 have already been recognized as permanently disabled.

A Jewish News Syndicate report notes that “around 2,000 Israeli civilians, soldiers and police officers have had limbs amputated or become disabled in other ways since Oct. 7.”

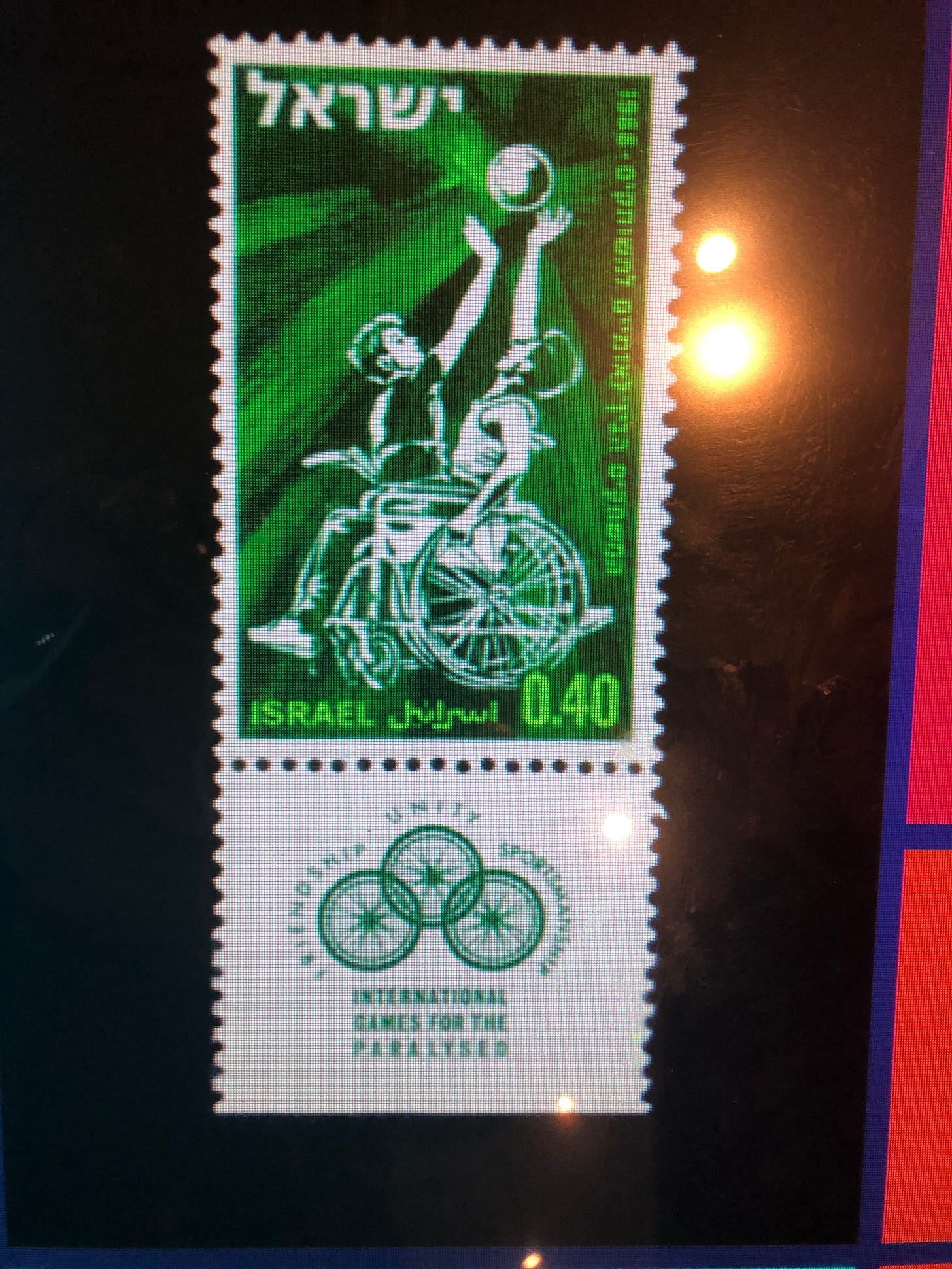

Due to previous wars, Israel has some experience in addressing the needs of mainly young people who have become disabled. Israel has a very active NGO, Negishut Israel/Access Israel, which has been advocating for the needs of the elderly and those with disabilities for decades. Organizations like Israel Para Sport Center introduces people with disabilities to sports.

In many ways, Israel is doing a great job addressing the needs of people with disabilities. The current war poses great challenges and opportunities to becoming a world leader in offering services guided by best practices for people with physical disabilities and mental health challenges. I pray Israel will continue to be a pioneer and leader.

Howard Blas has a wide range of professional and personal interests. He currently serves as director of the National Ramah Tikvah Network of the National Ramah Commission. In this capacity, Howard works with Ramah camps as they include and support campers with disabilities. Howard previously served as the director of the Tikvah Program at Camp Ramah in New England for 15 years. Howard discovered his passion for working with people with disabilities when he served as a counselor and division head in the Tikvah Program starting in the early 1980s.

From Rabbi Michael Levy:

Thank you for featuring Y in your JDIN post. We can help Y and others like him by introducing them to the independent living philosophy. Here are some core concepts.

Disability is not “The Problem”

We who have disabilities know that while health issues can be severe, the ongoing challenges involve the architectural, transportation, communication and attitudinal barriers that we face.

A Difficult Attitudinal Phenomenon:

When I am with a nondisabled friend, it is common for waiters to ask, “What would he like to eat?” To many health professionals ask, “Why is he here?” Even some clergy and other educators address our non-disabled companions in our presence as if we the disabled have become children.

I pray that Y has the fortitude to withstand the challenges mentioned above, and that Howard and others constantly espouse the independent living philosophy in Israel and elsewhere.